Cardiology (Y2)

Question 1:

Answer: B) Cardiac MRI

Explanation:

In cases where transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is limited due to poor acoustic windows (e.g., obesity, lung interference), Cardiac MRI (CMR) is the best alternative for detailed myocardial tissue characterisation, ventricular volume assessment, and overall cardiac function. It provides high spatial resolution, good temporal resolution, and is non-ionising. MRI scans have the best contrast resolution, CT scans have the best spatial resolution & echocardiograms have the best temporal resolution.

• Stress echocardiography (A) is useful for ischemia evaluation but does not address poor image quality issues.

• Transoesophageal echocardiography (C) offers better resolution than TTE but is primarily used for valvular pathology and left atrial structures rather than global ventricular assessment.

• Cardiac CT (D) provides excellent spatial resolution but lacks detailed myocardial tissue characterisation and is not the gold standard for ventricular function.

• Nuclear perfusion scan (E) is mainly used for ischemia assessment and has lower resolution for structural details.

Question 2:

Answer: C) Cardiac CT

Explanation:

Cardiac CT, specifically coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring, is the best initial test for low-risk patients with suspected coronary artery disease. It is a non-contrast CT scan that quantifies calcium deposits in the coronary arteries and has a high negative predictive value, making it effective at ruling out significant CAD.

• (A) Echocardiography: Primarily assesses cardiac function and valve disease but does not evaluate coronary artery plaque burden.

• (B) ECG: Useful for detecting acute ischemia but has poor sensitivity for stable CAD.

• (D) Cardiac MRI: Excellent for myocardial tissue characterisation but not the first-line test for ruling out CAD in low-risk patients.

• (E) Ultrasound: Used for vascular imaging (e.g., carotid arteries) but is not suitable for coronary artery assessment.

Question 3:

Answer: c) Partial Anterior Circulation Stroke (PACS – MCA territory)

Explanation:

This patient’s presentation includes contralateral hemiplegia, contralateral sensory loss (affecting the upper limb and face more than the lower limb), and expressive (Broca’s) aphasia, which suggests involvement of the middle cerebral artery (MCA).

• a) TACS: Requires all three of the following: hemiplegia, homonymous hemianopia, and higher cognitive dysfunction. This patient does not have homonymous hemianopia, ruling out TACS.

• b) PACS (ACA territory): Would cause more significant lower limb weakness and may involve abulia (lack of motivation). This patient primarily has upper limb and face involvement, making MCA territory more likely.

• d) PCS: Would present with contralateral homonymous hemianopia with macular sparing, visual agnosia, or vertigo with ataxia. This is not present in this patient.

• e) LACS: Typically presents with pure motor or pure sensory deficits, without higher cortical dysfunction (e.g., aphasia). The presence of expressive aphasia suggests cortical involvement, ruling out LACS.

Question 4:

Answer: b) Administer intravenous glucose

Explanation:

The FAST tool is commonly used by paramedics to identify stroke, but it is crucial to rule out stroke mimics before proceeding with stroke management. Hypoglycaemia (<3.5 mmol/L) can present with neurological deficits, including facial droop and slurred speech, mimicking a stroke. The priority in this case is to correct the glucose level first.

• a) CT brain scan: While necessary for confirming stroke, it is not the immediate priority before correcting glucose levels.

• c) NIHSS score: This assesses stroke severity but should only be used once stroke is confirmed.

• d) Thrombolysis: Should only be given after a confirmed diagnosis of ischaemic stroke and exclusion of mimics like hypoglycaemia.

• e) Carotid Doppler: Useful for assessing carotid stenosis in stroke patients but is not relevant in this acute setting.

Question 5:

Answer: d) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Explanation:

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the second most common cardiomyopathy and is a leading cause of sudden cardiac death in young athletes. It is caused by autosomal dominant mutations in sarcomeric proteins like MYBPC3 and MYH7. Key clinical features include:

• Concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (including the septum), leading to left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

• Decreased left ventricular end-diastolic volume

• Systolic murmur (due to dynamic obstruction) and S4 gallop

• Exertional syncope due to reduced cardiac output

Management involves medications (e.g., beta-blockers) and surgical intervention for outflow tract obstruction (e.g., septal alcohol ablation). Avoid medications that reduce preload (e.g., ACE inhibitors, diuretics) as they worsen obstruction.

Other options:

• a) Dilated cardiomyopathy → Presents with LV dilation and reduced ejection fraction (not hypertrophy)

• b) Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy → Typically affects the right ventricle, with fibrofatty replacement leading to arrhythmias

• c) Restrictive cardiomyopathy → Characterised by severe diastolic dysfunction and atrial enlargement, not asymmetric hypertrophy

• e) Ischaemic cardiomyopathy → Due to coronary artery disease, typically in older patients with history of MI

Question 6:

Answer: c) Pericarditis

Explanation:

Acute pericarditis is an inflammation of the pericardium that presents with:

• Pleuritic chest pain (sharp, retrosternal, worsens with inspiration, improves when sitting forward)

• Pericardial friction rub (best heard at the left sternal border with the patient leaning forward)

• Possible pericardial effusion, which can cause faint heart sounds

• ECG changes (diffuse ST elevation, PR depression)

Causes include viral infections (Coxsackie B), autoimmune conditions (SLE, rheumatoid arthritis), post-MI (Dressler’s syndrome), malignancy, and uraemia.

Other options:

• a) Myocardial infarction → Classically presents with crushing, pressure-like chest pain, not pleuritic pain that improves when sitting forward

• b) Pulmonary embolism → Can cause pleuritic chest pain but is often associated with tachycardia, dyspnoea, and hypoxia

• d) Aortic dissection → Presents with sudden, tearing chest pain radiating to the back, often in hypertensive patients

• e) Pneumothorax → Presents with sudden onset pleuritic chest pain and absent breath sounds on the affected side

Management:

• NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen, aspirin) for symptom relief

• Colchicine to prevent recurrence

• Antibiotics if bacterial pericarditis is suspected

Question 7:

Answer: a) Sacubitril/Valsartan (Neprilysin Inhibitor)

Explanation:

This patient with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), worsening symptoms, and an ejection fraction of 30% is an ideal candidate for sacubitril/valsartan (a neprilysin inhibitor combined with an angiotensin receptor blocker). Sacubitril/valsartan has been shown to significantly reduce mortality and hospitalisation rates in patients with HFrEFwhen added to standard therapy, including ACE inhibitors or ARBs and β-blockers. It works by inhibiting neprilysin, the enzyme responsible for breaking down brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), a potent vasodilator that promotes sodium excretion. The combined effect of valsartan and sacubitril leads to improved vasodilation, reduced blood volume, and decreased afterload, all of which are critical in managing heart failure.

Other options:

• b) Hydralazine → Hydralazine is an arterial vasodilator that can be used to reduce afterload, but it is typically used when patients cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors or ARBs, or in combination with nitrates in African-American patients with heart failure. It does not have the same robust evidence for mortality benefit as neprilysin inhibitors.

• c) Digoxin → Digoxin can increase contractility and decrease conduction velocity, but its primary role is in controlling atrial fibrillation with heart failure. It does not improve overall mortality and is used more for symptom control.

• d) Dobutamine → Dobutamine is a positive inotropic agent used in acute heart failure or severe decompensation requiring inotropic support. It is not used as a chronic therapy and can increase the risk of arrhythmias.

• e) Ivabradine → Ivabradine is used in heart failure with sinus rhythm and an ejection fraction <35% to reduce heart rate in symptomatic patients who remain symptomatic despite adequate β-blocker therapy. While useful in certain patients, it would not be the first choice in this case as sacubitril/valsartan would address the underlying pathophysiology more effectively.

Management of Chronic Heart Failure (HFrEF):

Optimal management typically includes a combination of RAAS inhibitors (ACE inhibitors or ARBs), β-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, and in certain cases, sacubitril/valsartan or neprilysin inhibitors to improve outcomes and reduce hospitalisations. Device therapy such as CRT or ICD may also be considered in patients with severe symptoms.

Question 8:

Answer: a) Flecainide

Explanation:

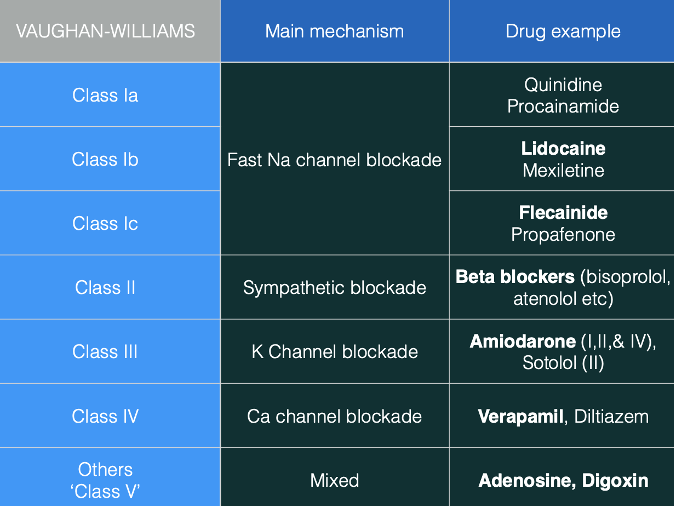

Flecainide is a Class I anti-arrhythmic that works by inhibiting sodium channels, thereby delaying the onset of myocardial depolarisation and increasing the myocardial refractory period. Flecainide is most commonly used for re-entrant supraventricular tachycardias (SVTs), especially in patients with atrial arrhythmias. It is especially effective in re-entrant SVTs but is not useful in nodal tissues because they lack sodium channels. Class I drugs are further divided into 1a, 1b, and 1c, with flecainide being a Class 1c drug (which has the most pronounced effect on depolarization and refractory periods).

Other options:

• b) Amiodarone → Amiodarone is a Class III anti-arrhythmic that has multiple actions (Class I, II, III, and IV), which prolong repolarisation (by blocking K+ channels) and the refractory period. It is effective in managing a variety of arrhythmias, including VT and atrial fibrillation. However, amiodarone is typically not the first-line drug for SVTs due to its side effects and the more specific efficacy of other drugs like flecainide.

• c) Lidocaine → Lidocaine is a Class 1b anti-arrhythmic typically used for ventricular arrhythmias (VTs) rather than SVTs. It works by inhibiting sodium channels but is not effective for arrhythmias involving nodal tissues, which are common in SVTs.

• d) Diltiazem → Diltiazem is a Class IV anti-arrhythmic that inhibits L-type calcium channels. It is effective in managing nodal arrhythmias like SVTs and atrial fibrillation by slowing conduction and reducing heart rate. However, it is not a sodium channel blocker and thus does not work as effectively for re-entrant arrhythmias as flecainide.

• e) Digoxin → Digoxin is a cardiac glycoside that increases vagal tone, reducing conduction velocity. It is used to manage atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter, particularly in rate control. While it can affect conduction in the AV node, it is not commonly used for re-entrant SVTs.

Question 9:

Answer: b) 2nd Degree AV Block, Mobitz I (Wenckebach)

Explanation:

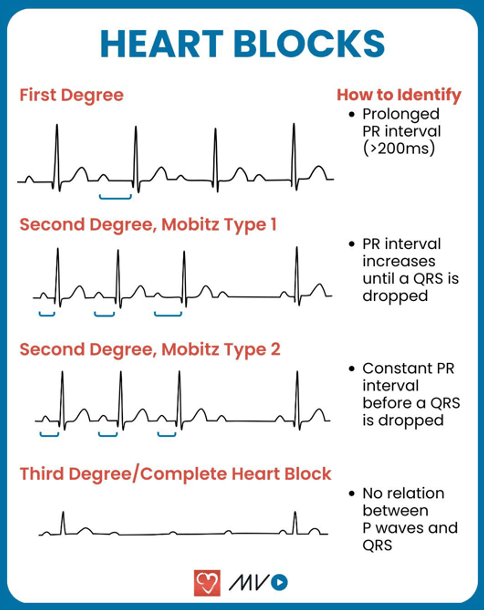

The key finding in this patient’s ECG is a prolonged PR interval of 400 ms, followed by a dropped QRS complex every second P wave. This pattern is characteristic of Mobitz I (Wenckebach), which is a type of 2nd Degree AV Block. In Mobitz I, the PR interval progressively lengthens until one P wave is not followed by a QRS complex, after which the cycle resets. The key distinguishing feature here is the progressive PR interval lengtheningbefore the drop in the QRS complex, which contrasts with Mobitz II where the PR interval remains fixed and a QRS complex is dropped after a set number of P waves.

Other options:

• a) 1st Degree AV Block → In 1st Degree AV Block, the PR interval is prolonged but constant throughout the rhythm, unlike Mobitz I where the PR interval progressively lengthens before a dropped beat. No QRS complexes are dropped in 1st Degree AV Block.

• c) 2nd Degree AV Block, Mobitz II → In Mobitz II, the PR interval is fixed and not progressively prolonged. The characteristic feature is the dropped QRS complex after a fixed number of P waves (e.g., every 2nd or 3rd P wave), without any gradual increase in PR interval. This is different from the progressive PR interval lengthening seen in Mobitz I.

• d) 3rd Degree AV Block → In 3rd Degree AV Block (complete block), there is no communication between the atria and the ventricles. This results in AV dissociation, where P waves and QRS complexes are completely independent, and there is no consistent pattern of dropped QRS complexes following P waves as seen in 2nd Degree AV Block. The PR interval is not fixed or prolonged in the same way as Mobitz I or II.

• e) Left Bundle Branch Block (LBBB) → In LBBB, the conduction delay affects the left bundle branch, causing a widened QRS complex (>120 ms) due to delayed left ventricular depolarisation. This does not typically result in dropped QRS complexesfollowing P waves, and the pattern of PR interval prolongation followed by a dropped QRS complex does not fit the description of a bundle branch block.

Question 10:

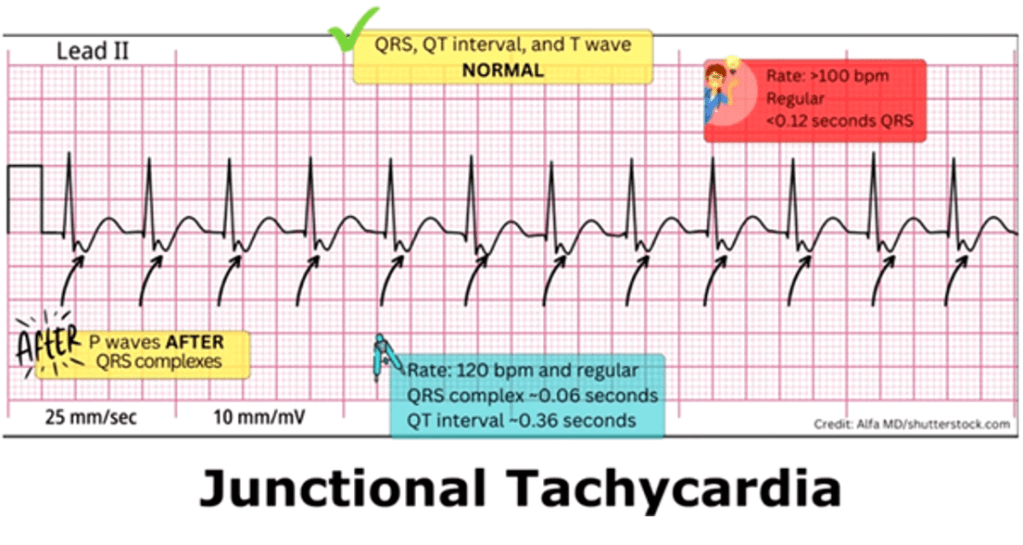

Answer: c) Re-entry circuit within the atrioventricular node

Explanation:

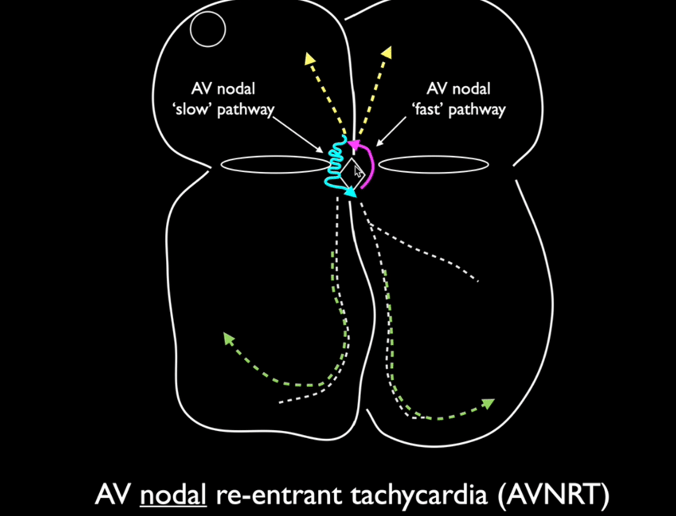

This patient’s sudden-onset regular, narrow QRS tachycardia with an absence of visible P waves is highly suggestive of Atrioventricular Nodal Re-entrant Tachycardia (AVNRT), the most common type of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT).

• In AVNRT, there is an abnormal re-entry circuit within the AV node that allows impulses to continuously cycle between a slow and a fast pathway, leading to rapid ventricular activation.

• The P waves are often buried within or occur just after the QRS complex, making them difficult to see.

• The ECG shows a narrow QRS complex tachycardia, unless a bundle branch block is present.

• Symptoms are usually palpitations, dizziness, and sometimes syncope, but it is generally not life-threatening.

• Vagal manoeuvres (e.g., carotid sinus massage, Valsalva) may terminate the arrhythmia by increasing vagal tone and blocking AV nodal conduction. If unsuccessful, adenosine is used to interrupt AV nodal conduction.

• Definitive treatment involves catheter ablation of the accessory pathway.

Why not the other options?

• a) Enhanced automaticity of an ectopic atrial focus → Would cause focal atrial tachycardia, which typically shows abnormal P waves before each QRS complexwith a consistent morphology.

• b) Atrial fibrillation originating from pulmonary veins → Would present with an irregularly irregular rhythm and no distinct P waves, rather than a regular tachycardia.

• d) Ventricular pre-excitation due to an accessory pathway → Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome involves a bypass tract (e.g., Bundle of Kent) that leads to pre-excitation of the ventricles, causing a delta wave on ECG. This patient’s ECG does not show a delta wave, and WPW can cause both orthodromic and antidromic tachycardias, which can be regular or irregular.

• e) Delayed afterdepolarisations triggering focal atrial tachycardia → More commonly associated with digoxin toxicity or catecholamine excess, leading to multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT) with at least three different P wave morphologies, which is not seen here.

Question 11:

Answer: b) Disorganised electrical activity from multiple foci in the atria

Explanation:

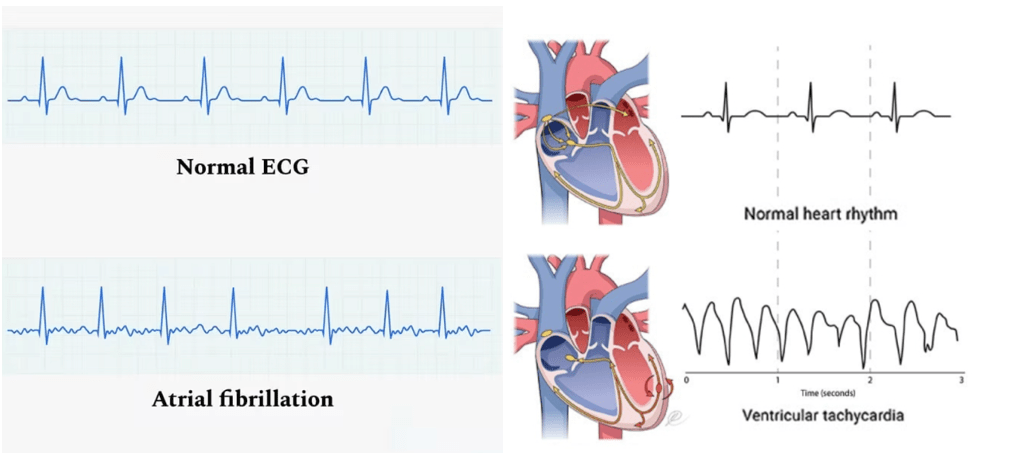

This patient’s symptoms and ECG findings are characteristic of atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common sustained arrhythmia. AF occurs due to multiple ectopic foci, predominantly originating from the pulmonary veins in the left atrium, creating disorganised electrical activity and preventing coordinated atrial contraction.

• The hallmark ECG findings of AF include:

o Absent P waves (due to chaotic atrial activity)

o Irregularly irregular R-R intervals

o Narrow QRS complexes (unless a bundle branch block or accessory pathway is present)

• Risk factors for AF include hypertension, heart failure, valvular disease, systemic infections, and thyroid disease.

• AF increases the risk of thromboembolic events (e.g., stroke) due to stasis of blood in the atria.

Why not the other options?

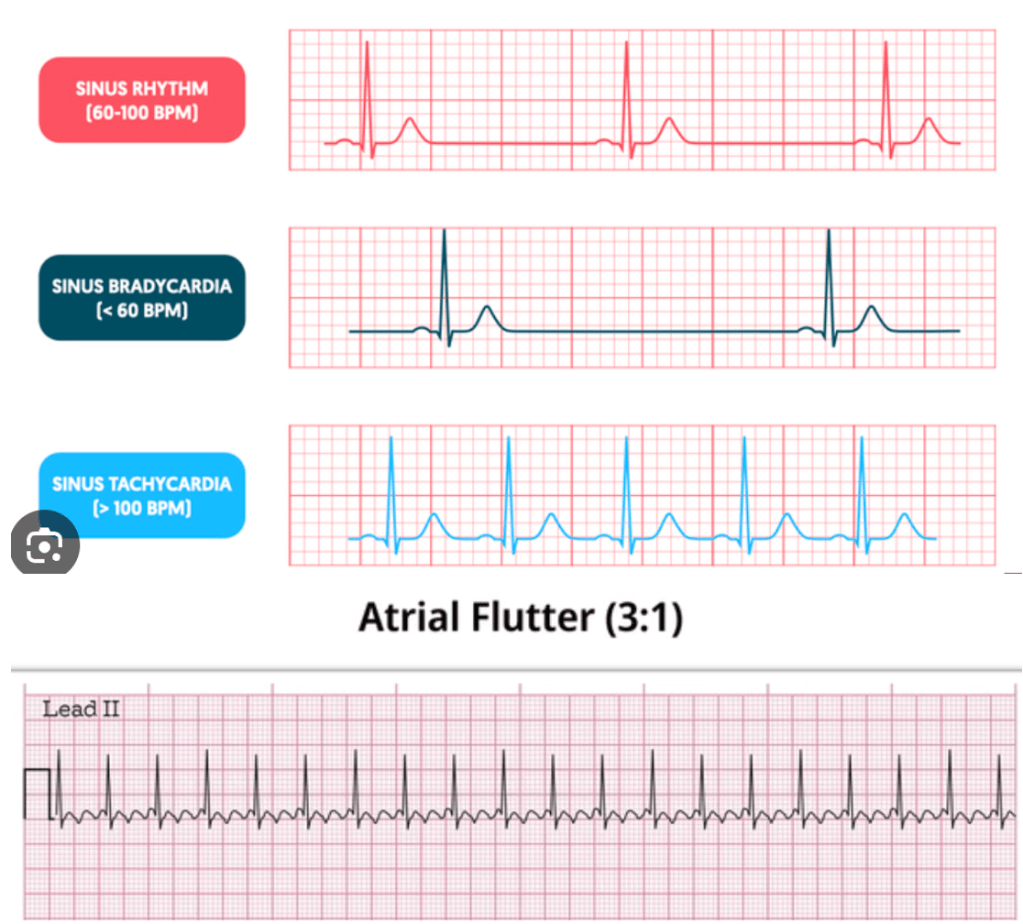

• a) A single re-entrant circuit around the tricuspid isthmus → Describes atrial flutter, which produces a sawtooth pattern (F-waves) in Lead II with a regular conduction ratio (e.g., 2:1 AV block = ventricular rate of 150 bpm).

• c) A rapidly firing ectopic atrial focus → More consistent with focal atrial tachycardia, which shows a single P wave morphology before each QRS.

• d) Pre-excitation of the atria through an accessory pathway → Suggests Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, which presents with a delta wave, short PR interval, and episodes of tachyarrhythmia (AVRT).

• e) Enhanced automaticity of the sinoatrial node → Would lead to sinus tachycardia, which maintains a normal P wave before each QRS complex.

Question 12:

Answer: d) Immediate defibrillation

Explanation:

This patient presents with ventricular fibrillation (VF), a life-threatening arrhythmia characterised by disorganised electrical activity, loss of cardiac output, and immediate risk of death. The only effective treatment for VF is immediate defibrillation, as it allows the heart to reset and potentially resume a normal rhythm.

• ECG Findings in VF:

o No discernible rate or rhythm

o Absence of P waves, QRS complexes, or T waves

o Chaotic electrical activity

• Causes of VF:

o Acute myocardial infarction

o Inherited channelopathies (e.g., Brugada syndrome, Long QT syndrome)

o Electrolyte imbalances (hypokalaemia, hypomagnesemia)

o Cardiac trauma, myocarditis, endocarditis

Why not the other options?

• a) Intravenous β-blockers → Contraindicated in VF as they do not restore a perfusing rhythm and can worsen hypotension.

• b) Intravenous magnesium sulphate → Used for Torsades de Pointes (a subtype of polymorphic VT), not for VF.

• c) Synchronised cardioversion → Indicated for unstable atrial fibrillation or VT with a pulse, but VF requires unsynchronised defibrillation.

• e) Atropine and transcutaneous pacing → Used for bradyarrhythmias (e.g., complete heart block), not VF.

Question 13:

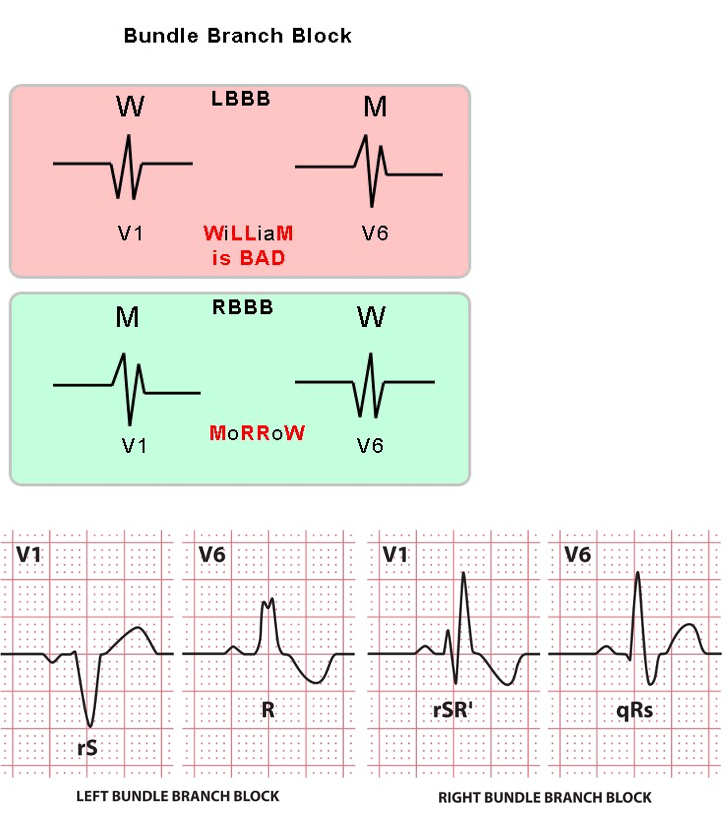

Answer: b) Right Bundle Branch Block (RBBB)

Explanation:

This patient’s ECG shows a broad QRS complex (>120ms) with an M-shaped R wave in leads V1 and V2, which is diagnostic of Right Bundle Branch Block (RBBB).

• Key Features of RBBB on ECG:

o Wide QRS complex (>120 ms)

o M-shaped (rsR‘) pattern in leads V1 and V2

o Wide/slurred S wave in leads I, V5, and V6

o May be benign or associated with right heart pathology (e.g., pulmonary hypertension, atrial septal defect).

• Why not the other options?

o a) Left Bundle Branch Block (LBBB) → Characterised by a broad QRS, large R wave in V5/V6, and left axis deviation, not an M-shaped pattern in V1/V2.

o c) Ventricular Tachycardia → Typically presents with wide, regular QRS complexes without a clear bundle branch block pattern.

o d) Atrial Flutter → Characterised by sawtooth F-waves in lead II and does not typically cause a wide QRS unless there is a bundle branch block.

o e) Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome → Shows a short PR interval and delta wave (slurred upstroke of the QRS complex).

Question 14:

Answer: b) Iron deficiency anaemia

Explanation:

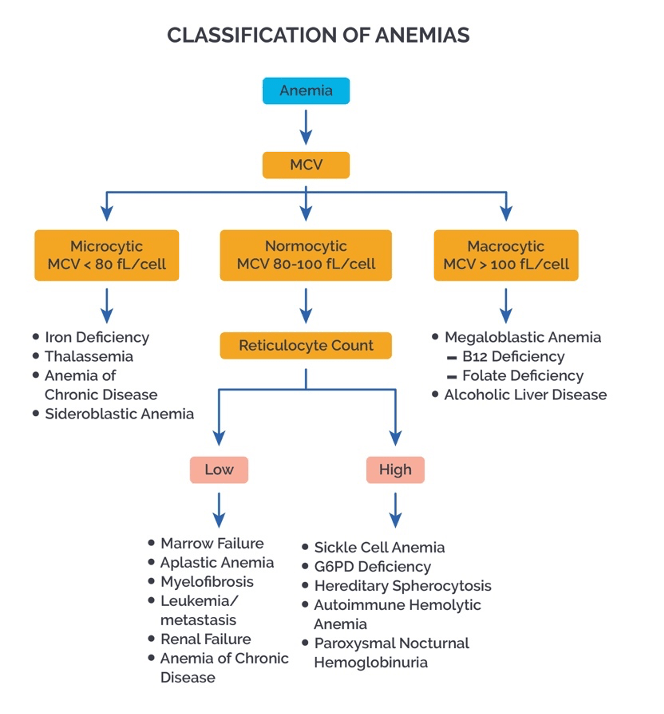

This patient’s low MCV, low MCH, increased RCDW, and low haematocrit suggest iron deficiency anaemia.

• Key Findings in Iron Deficiency Anaemia:

o Low MCV (<80 fL) → Microcytosis (small RBCs due to insufficient haemoglobin production).

o Low MCH → Reduced amount of haemoglobin per RBC.

o Increased RCDW → High variability in RBC size due to a mix of normal and microcytic cells.

o Low haematocrit → Reduced RBC mass.

• Why not the other options?

o a) Vitamin B12 deficiency → Causes macrocytic anaemia (high MCV, normal or high MCH, normal RCDW).

o c) Chronic kidney disease → Typically presents with normocytic anaemia(normal MCV, normal MCH) due to decreased erythropoietin.

o d) Aplastic anaemia → Characterised by pancytopenia (low RBCs, WBCs, and platelets) with normal or slightly low MCV.

o e) Hereditary spherocytosis → Causes increased MCHC and normal or slightly decreased MCV, rather than the classic low MCV/MCH seen in iron deficiency.

Clinical Significance:

Iron deficiency anaemia is the most common cause of microcytic anaemia, often due to chronic blood loss (e.g., gastrointestinal bleeding, heavy menstruation) or insufficient dietary intake. Treatment involves addressing the underlying cause and iron supplementation.

(*)

Question 15:

Answer: b) Transferrin transports iron in the blood, while ferritin stores it in the liver

Explanation:

Iron is essential for erythropoiesis and is tightly regulated:

• Iron Transport:

o Transferrin → Binds free iron in the blood and delivers it to the bone marrow for RBC production or to the liver for storage.

• Iron Storage:

o Ferritin → Acts as an iron buffer, storing excess iron in the liver and releasing it when needed.

• Erythrocyte Breakdown:

o When RBCs are degraded, haemoglobin is released and binds to haptoglobinto prevent free haemoglobin toxicity.

o Heme is oxidised to biliverdin, then converted to bilirubin and excreted via bile.

o Iron is recycled and transported by transferrin for reuse.

Why not the other options?

• a) Haptoglobin binds free iron → Incorrect, haptoglobin binds free haemoglobin, not iron.

• c) Haemoglobin is broken into biliverdin and stored in the spleen → Incorrect, biliverdin is converted to bilirubin and excreted, not stored.

• d) Reticulocytes retain their nuclei for iron storage → Incorrect, reticulocytes do not store iron; they lose their nuclei before maturing.

• e) Hemopexin binds free globin chains → Incorrect, hemopexin binds free heme, not globin chains.

Question 16:

Answer: c) Acute myeloid leukaemia

Explanation:

The patient presents with pancytopenia (anaemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopaenia), alongside hepatosplenomegaly and a high percentage of immature blast cells in the bone marrow (>30%). This is characteristic of Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML).

Pathophysiology:

• AML is a malignancy of myeloid stem cells, leading to the accumulation of immature myeloid blasts in the bone marrow.

• This prevents normal haematopoiesis, causing anaemia (fatigue, pallor), leukopenia (infections), and thrombocytopaenia (bruising, bleeding tendencies).

• The presence of >30% blasts in the bone marrow confirms acute leukaemia.

Why not the other options?

• a) Aplastic anaemia → Also presents with pancytopenia, but it is due to bone marrow failure rather than malignant infiltration. There would be hypocellular marrow instead of blast proliferation.

• b) Myelodysplastic syndrome → Can lead to pancytopenia but is a pre-leukaemic condition. It features dysplastic (abnormal) cells rather than a high blast count.

• d) Hodgkin’s lymphoma → Affects lymph nodes, not bone marrow primarily. Presents with B symptoms (night sweats, fever, weight loss) rather than pancytopenia.

• e) Multiple myeloma → Characterised by monoclonal antibodies (IgG, IgA), hypercalcaemia, bone lesions, and kidney injury rather than a high blast count.

Question 17:

Answer: b) Increased intravascular haemolysis leading to haemoglobinemia

Explanation:

The patient’s presentation with jaundice, dark urine (haemoglobinuria), elevated reticulocytes, and low haptoglobin/hemopexin is consistent with intravascular haemolysis.

Physiological Mechanism of Intravascular Haemolysis:

• RBCs are destroyed within blood vessels, releasing free haemoglobin into plasma(haemoglobinemia).

• Free haemoglobin binds to haptoglobin, but once haptoglobin is depleted, excess haemoglobin binds to hemopexin and then albumin (methaemalbuminaemia).

• Haemoglobinuria occurs when plasma haemoglobin exceeds renal reabsorption capacity, leading to dark urine.

• Haemosiderinuria occurs when renal tubules absorb and degrade haemoglobin, storing iron as haemosiderin, which is then excreted.

Why not the other options?

• a) Extravascular haemolysis → More common in the spleen and liver. Does not cause haemoglobinuria or haemosiderinuria since RBCs are degraded intracellularly rather than releasing free haemoglobin into plasma.

• c) Bone marrow failure → Would cause pancytopenia, not haemolysis.

• d) Defective haemoglobin synthesis (e.g., thalassemia, iron deficiency) → Would present with microcytosis, not haemolysis.

• e) Autoimmune destruction of erythroid precursors → Suggestive of pure red cell aplasia, which causes anaemia due to impaired production, not increased destruction.

Question 18:

Answer:

b) Slowly activating potassium channel (IKs)

Explanation:

• IKs (Kv7.1) is a slowly activating potassium channel responsible for late repolarisation during phase 3 of the action potential. Mutations in the IKs channel gene (KVLQT1) are associated with Long QT syndrome type 1. This variant of Long QT syndrome typically presents with symptoms during exercise or physical activity, when the increased sympathetic drive accentuates the prolonged repolarisation and triggers arrhythmias like Torsades de Pointes.

• Symptoms like fainting during exercise are commonly observed in Long QT syndrome type 1, which results from impaired function of the IKs channel.

Why not the other options?

• a) Rapidly activating potassium channel (IKr): Dysfunction in the IKr channel is more commonly associated with Long QT syndrome type 2, which can also cause Torsades de Pointes, but it tends to have less exercise-related symptoms compared to IKs mutations e.g during rest (much more serious).

• c) Inward rectifier potassium channel (IK1): IK1 is involved in maintaining the resting membrane potential and does not play a major role in repolarisation. It’s not typically associated with Long QT syndrome.

• d) ATP-sensitive potassium channel (KATP): KATP channels are involved in metabolism-dependent regulation of the action potential but are not the primary channel involved in Long QT syndrome or exercise-induced arrhythmias.

• e) Calcium-activated potassium channel (KCa): KCa channels are important for regulating vascular smooth muscle function and action potential duration in other tissues, but they are not commonly implicated in Long QT syndrome or in exercise-triggered arrhythmias.

Clinical Relevance:

• Long QT syndrome (associated with mutations in IKs) is a genetic arrhythmia disorder that can lead to fatal arrhythmias like Torsades de Pointes, especially when symptoms occur during physical exertion.

• Torsades de Pointes is a polymorphic ventricular tachycardia often triggered by a prolonged QT interval and can lead to sudden cardiac death if not treated.

Question 19:

Answer: c) Oxygen consumption (VO2) should be less than oxygen delivery (DO2), and during exercise, both increase in response to higher metabolic demand.

Explanation:

• SvO2 (mixed venous oxygen saturation) reflects the oxygen saturation of blood returning to the heart. Normal SvO2 values range from 75% to 65%. A lower SvO2 indicates that the tissues are extracting more oxygen from the blood, which could happen in conditions like exercise or tissue hypoxia.

• Global oxygen delivery (DO2) refers to the total amount of oxygen delivered to tissues per minute and is dependent on cardiac output. As cardiac output increases (as it does during exercise), both DO2 and VO2 increase to meet the higher metabolic demands of tissues.

• VO2 (oxygen consumption) represents the total amount of oxygen consumed by tissues for oxidative metabolism. In a healthy individual, DO2 > VO2 because the body ensures an adequate oxygen supply to meet the metabolic needs of tissues.

Why not the other options?

• a) A low SvO2 indicates that oxygen consumption exceeds oxygen delivery to tissues, resulting in fatigue.

o Incorrect. A low SvO2 could indicate high oxygen extraction by tissues, but not necessarily that VO2 exceeds DO2, especially during exercise when both increase simultaneously to meet metabolic demand.

• b) SvO2 is directly proportional to cardiac output, but does not reflect tissue oxygen extraction.

o Incorrect. SvO2 does reflect tissue oxygen extraction as it indicates the balance between the oxygen delivered to tissues (DO2) and the oxygen consumed by tissues (VO2). A decrease in SvO2 typically indicates higher tissue oxygen extraction.

• d) A SvO2 of 70% indicates a significant oxygen deficit, suggesting impaired tissue oxygen delivery.

o Incorrect. A SvO2 of 70% is within the normal range (65-75%) and does not necessarily indicate an oxygen deficit. It suggests a typical level of oxygen extraction from the blood by tissues.

• e) Venous oxygen content (CV(O2)) decreases during exercise, leading to decreased oxygen availability to tissues.

o Incorrect. During exercise, oxygen consumption increases, which leads to a higher oxygen extraction from the blood, but CV(O2) does not necessarily decrease. Instead, DO2 increases to ensure adequate oxygen delivery to tissues.

Clinical Relevance:

• SvO2 and DO2 are important clinical parameters used to assess the adequacy of oxygen delivery in critically ill patients and can guide therapy in conditions such as shock or heart failure.

• During exercise, there is an increase in cardiac output and oxygen consumption to meet the metabolic needs of tissues. This is why SvO2, DO2, and VO2 increase during physical activity.

Question 20:

Answer: a) Increased levels of 2,3-DPG in response to low ambient oxygen levels

Explanation:

At high altitudes, there is reduced oxygen availability, leading to a compensatory increase in the production of 2,3-Diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG) in red blood cells. The increased 2,3-DPG binds to haemoglobin, which reduces its affinity for oxygen, allowing for more oxygen to be delivered to tissues. This is a physiological adaptation to low oxygen levels at high altitude, and it typically causes a rightward shift in the oxygen-haemoglobin dissociation curve. The body uses this mechanism to improve oxygen unloading in tissues that need it most during conditions of hypoxia.

Why not the other options?

b) Decreased pCO2 due to hyperventilation: Hyperventilation at high altitude leads to decreased pCO2 (respiratory alkalosis), which would typically cause a leftward shift in the oxygen-haemoglobin dissociation curve, increasing haemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen. This is not the primary adaptation to hypoxia at high altitudes, where the body uses 2,3-DPG to facilitate oxygen release.

c) Reduced pH due to hypoventilation: Hypoventilation would cause an increase in pCO2 and a drop in pH (acidosis), which would shift the curve to the right. However, this patient is more likely hyperventilating to compensate for the low oxygen levels, leading to respiratory alkalosis rather than acidosis.

d) Increased oxygen saturation due to improved lung oxygen exchange: While improved oxygen saturation may occur due to breathing more oxygen-rich air at high altitudes, this factor does not directly alter the oxygen-haemoglobin dissociation curve. The key physiological response to low oxygen at high altitudes is the increase in 2,3-DPG, which shifts the curve and promotes oxygen release.

e) Increased haemoglobin affinity for oxygen due to low temperature: Lower temperatures would lead to a leftward shift in the oxygen-haemoglobin dissociation curve, which increases the affinity of haemoglobin for oxygen. However, at high altitudes, the physiological response is to decrease haemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen through increased 2,3-DPG, which facilitates oxygen unloading to tissues.

Question 21:

Answer: b) Venous valve incompetence and chronic venous hypertension

Explanation:

This patient’s symptoms are consistent with venous insufficiency and venous ulcers. The characteristic findings in venous insufficiency include:

• Location of ulcers: Ulcers are typically located above the medial or lateral malleolus, which matches the location of this patient’s ulcer.

• Skin changes: The skin is described as thickened, mottled, and pigmented, which is typical of chronic venous stasis.

• Swelling: Swelling, especially at the end of the day, is common in venous insufficiency due to fluid accumulation from poor venous return.

• Moderate pain: The ulcer is moderately painful, which is typical for venous ulcers, and elevating the legs often helps relieve the pain.

• Normal pulses: This suggests that the issue is venous, rather than arterial (where pulses would typically be diminished).

The pathophysiology of venous insufficiency is related to impaired venous return due to venous valve incompetence, which leads to venous hypertension. This increased pressure in the veins causes congestion in the surrounding tissues and leads to the formation of ulcers. The condition can be worsened by factors such as diabetes and hypertension, both of which the patient has.

Why not the other options?

a) Decreased blood flow to tissues due to atherosclerosis: This describes arterial insufficiency, where poor arterial blood supply leads to ischemia and tissue necrosis. However, this patient does not exhibit signs like cold, hairless, shiny skin or pallor upon elevation, which would be characteristic of arterial insufficiency.

c) Intermittent claudication due to ischemia from arteriosclerosis: Intermittent claudicationoccurs in arterial insufficiency, where a patient experiences sharp, stabbing pain, especially with exertion. This patient’s pain is described as more of an aching or crampingpain, which typically occurs in venous insufficiency.

d) Peripheral neuropathy and diminished sensation leading to ulcer formation: While peripheral neuropathy (often seen in diabetic patients) can contribute to ulcer formation, the location of the ulcer and skin changes (thickening, mottling, pigmentation) in this case point more towards venous insufficiency than to neuropathic ulcers, which are often painless and occur at pressure points.

e) Systemic vasculitis affecting small vessels in the legs: While vasculitis can cause ulcers, this patient’s presentation with mottled skin, varicose veins, and normal pulses is more consistent with venous insufficiency. Vasculitis would typically cause more widespread inflammation and would present with more systemic symptoms, such as fever or a history of autoimmune diseases.

Question 22:

Answer:a) Administer 300mg Aspirin and GTN spray

Explanation:

In the pre-hospital setting for acute coronary syndrome (ACS), the immediate managementfocuses on antiplatelet therapy and pain relief. The 300mg of aspirin should be administered as soon as ACS is suspected to inhibit platelet aggregation, and the GTN sprayshould be used for pain relief by reducing myocardial oxygen demand through vasodilation.

The rationale for these interventions is to prevent further thrombosis in the coronary arteries and reduce the work of the heart while awaiting further medical care. The use of aspirin early on helps to prevent further clot formation, while GTN spray relieves chest pain.

Why not the other options?

b) Administer morphine and oxygen, followed by 75mg of Aspirin: Oxygen is indicated only if the patient’s resting oxygen saturation is below 95%. Morphine can be used in the hospital setting for pain relief but is not part of the pre-hospital management for this acute phase. The initial dose of Aspirin should be 300mg, not 75mg, in the pre-hospital setting.

c) Administer 600mg Aspirin and initiate dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel: 600mg aspirin is usually given if primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is planned, but it is not a standard dose for initial pre-hospital management. Dual antiplatelet therapy(DAPT) with clopidogrel or other agents is typically started in-hospital once the diagnosis is confirmed, not in the pre-hospital phase.

d) Administer morphine + metoclopramide and oxygen: Oxygen should be given only if the patient’s oxygen saturation is below 95%, and this patient’s saturation is 98%, making this step unnecessary at the moment.

e) Initiate statin therapy and ACE inhibitors: While statins and ACE inhibitors are important in chronic ACS management, they are not part of the initial pre-hospital treatment for acute ACS. The focus in the acute setting is on antiplatelet therapy, pain relief, and oxygen support if needed.

Question 23:

Answer: b) Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (non-STEMI)

Explanation:

This patient’s presentation is most consistent with non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (non-STEMI). Key features supporting this diagnosis are:

• Chest pain: The patient’s chest pain is described as tight and crushing, which is typical of ischemic heart disease.

• Duration of pain: The pain lasted for 45 minutes, which is consistent with an acute ischemic event.

• Cardiac biomarkers: The elevated cardiac troponin levels indicate myocardial injury, confirming the diagnosis of a myocardial infarction.

• No ST-segment elevations on ECG: The absence of ST-segment elevations suggests that this is not a STEMI, but rather a non-STEMI, which is characterized by elevated cardiac biomarkers without ST-segment elevation.

Why not the other options?

a) Unstable Angina: Unstable angina is a form of acute coronary syndrome, but it does notcause significant myocardial injury, and cardiac biomarkers such as troponin would be normal. This patient’s elevated troponin suggests myocardial injury, making unstable angina unlikely.

c) ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI): A STEMI typically presents with ST-segment elevations on ECG, which this patient does not have. Therefore, STEMI is not consistent with this patient’s presentation.

d) Silent Myocardial Infarction: A silent myocardial infarction (often seen in diabetics or the elderly) typically lacks typical chest pain symptoms. This patient has acute chest pain, so this diagnosis is less likely.

e) Cocaine-induced Myocardial Ischaemia: While cocaine use can cause myocardial ischaemia due to vasospasms, it typically presents in younger individuals and is associated with acute onset chest pain and no ECG changes or transient ST-segment elevation. This patient’s age and symptoms do not strongly suggest cocaine-induced ischemia.

Question 24:

Answer: e) GRACE

Explanation:

The GRACE score (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) is used to assess the short-term and long-term risk in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), including both STEMI and non-STEMI. It takes into account various clinical parameters, such as age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, creatinine levels, cardiac arrest at presentation, and other factors that contribute to predicting mortality and adverse outcomes.

Key points:

• GRACE is specifically used for risk stratification in patients with ACS (including both STEMI and non-STEMI) to help guide clinical management.

• CRUSADE, on the other hand, is used to assess bleeding risk in non-STEMI patients, particularly in those receiving antiplatelet therapy.

Why not the other options?

a) CURB-65: This is used for community-acquired pneumonia to assess severity and need for inpatient care. It is not relevant to acute coronary syndrome.

b) CRUSADE: The CRUSADE score is used to assess the risk of bleeding in patients with non-STEMI and unstable angina undergoing antiplatelet therapy, not for overall risk assessment of ACS.

c) APACHE II: This score is used to assess the severity of illness in critically ill patients, particularly in ICU settings. It is not specific to ACS.

d) Wells Score: This score is used for the assessment of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), not for ACS.

Question 25:

Answer: c) Interventricular septum and moderator band

Explanation:

The Right Coronary Artery (RCA) typically supplies several key areas of the heart, including the right ventricle and inferior right margin. Additionally, it supplies the posterior interventricular artery (PIA) in the case of right dominance (which is the most common). The posterior interventricular artery supplies the interventricular septum and moderator band.

• Right dominance: In about 80% of the population, the posterior interventricular artery arises from the RCA, and it supplies the posterior part of the interventricular septum, which includes the moderator band. An occlusion of the RCA in such individuals would put these structures at risk of ischemia, which could lead to heart block and other conduction abnormalities.

• Why not the other options?

a) Left anterior surface of the heart: This is supplied by the Left Anterior Descending (LAD) artery, a branch of the left coronary artery, and would not be directly affected by an occlusion of the RCA.

b) Left posterior surface of the heart: This is typically supplied by the left circumflex artery (LCx), a branch of the left coronary artery, not the RCA.

d) SA node: The SA node is supplied by a branch of the right coronary artery in about 60%of the population, but this would only be at risk in cases of right coronary occlusion. This patient likely has a right-dominant coronary system, so SA node ischemia is a possible complication, but the interventricular septum is at more significant risk due to RCA occlusion.

e) AV node: The AV node is supplied by a branch of the RCA in approximately 80% of people, making it more likely to be affected by an occlusion of the RCA. However, the interventricular septum and moderator band are more directly affected by the occlusion of the posterior interventricular artery.

Question 26:

Answer: b) Leads I, aVL, V5-V6

Explanation:

The Left Circumflex Artery (LCx) primarily supplies the lateral wall of the left ventricle, including the left atrium and portions of the posterior wall of the left ventricle. An occlusion of the LCx typically leads to ischemic changes that are best reflected in the lateral leads of the ECG, specifically leads I, aVL, V5, and V6.

• Leads I, aVL, V5-V6: These leads correspond to the lateral wall of the heart, which is mainly supplied by the LCx. Ischemia from LCx occlusion would typically cause ST-segment depression or elevation in these leads.

Why not the other options?

a) Leads V1-V4: These leads correspond to the anterior wall of the heart, which is primarily supplied by the Left Anterior Descending (LAD) artery, not the LCx. Ischemia from LCxocclusion would not typically affect these leads.

c) Leads II, III, aVF: These leads correspond to the inferior wall of the heart, which is primarily supplied by the Right Coronary Artery (RCA) in right-dominant systems, or the LCx in left-dominant systems. However, these leads are less likely to be affected by an isolated LCx occlusion compared to the lateral leads.

d) Leads V3-V6, I, aVL: While leads V5-V6, I, and aVL are correct for lateral wall ischemia, leads V3-V4 correspond to the anterior wall, which is predominantly supplied by the LAD artery. Thus, including V3-V4 makes this option incorrect.

e) Leads V1, V2, aVF: Leads V1 and V2 correspond to the right ventricle and anterior wall, which are typically supplied by the RCA and LAD arteries, respectively. Lead aVF is more associated with the inferior wall, which is also not primarily affected by an LCxocclusion.

Question 27:

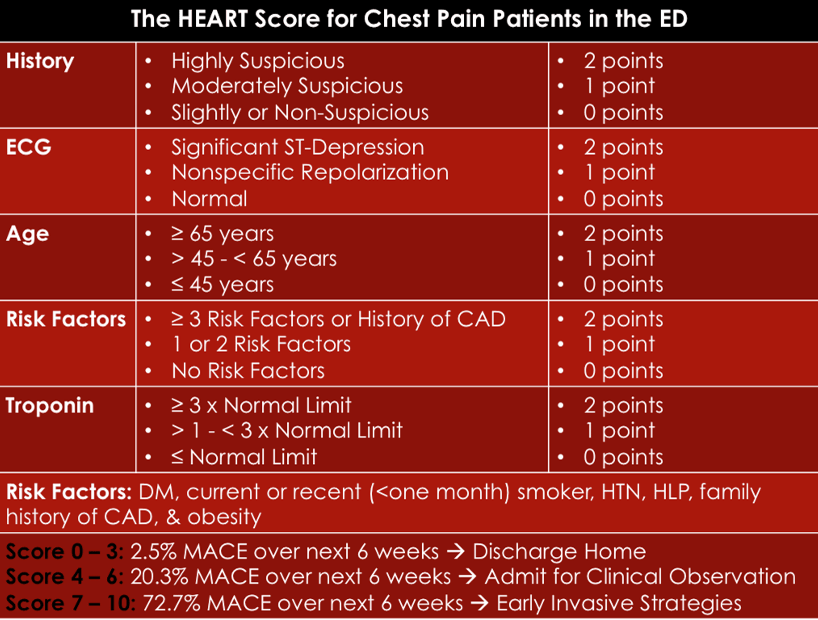

Answer: d) HEART Score

Explanation:

The HEART Score is specifically designed to assess the cause of chest pain and predict the likelihood of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), including Non-STEMI. It evaluates the following components:

• History: The nature of the chest pain (typical, atypical, or non-anginal)

• ECG: Presence of ST-segment changes

• Age: Age of the patient

• Risk factors: Hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, smoking, diabetes, etc.

• Troponin levels: Elevated or normal levels

The HEART Score is crucial in triaging patients with chest pain, helping to assess the likelihood of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), including Non-STEMI. It is used to guide decision-making on whether the chest pain is likely of cardiac origin and whether more invasive testing or interventions are necessary.

Why not the other options?

a) Killip Classification: This classification is used to assess the severity of heart failure after a STEMI, not for assessing the cause of chest pain in Non-STEMI or ACS patients.

b) TIMI Score: The TIMI Score is primarily used for risk stratification in STEMI and Non-STEMI patients, predicting the 14-day risk of death, myocardial infarction, or severe recurrent ischemia. It helps guide treatment decisions but does not assess the cause of chest pain.

c) GRACE Score: The GRACE Score is used to assess the 6-month risk of mortality and adverse outcomes in Non-STEMI patients. While it is helpful for risk stratification in high-risk patients, it does not specifically assess the cause of chest pain like the HEART Scoredoes.

e) APACHE II Score: The APACHE II Score is used to assess the severity of illness in critically ill patients, not specifically for evaluating chest pain or ACS.

Question 28:

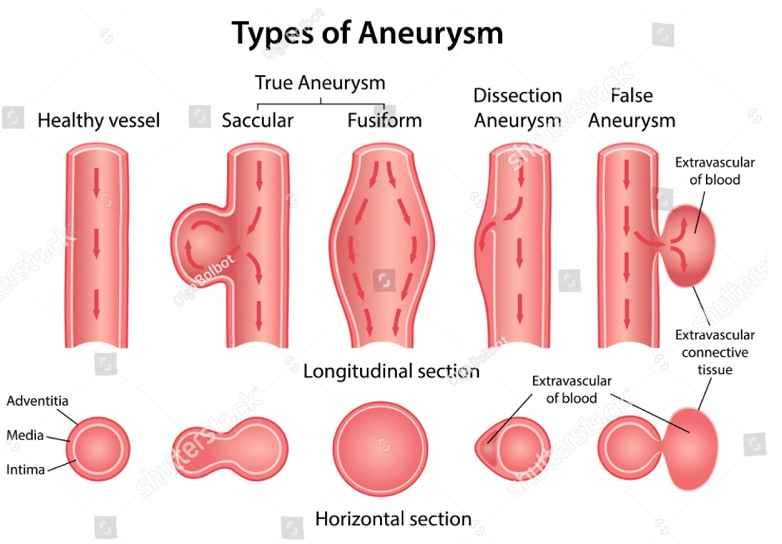

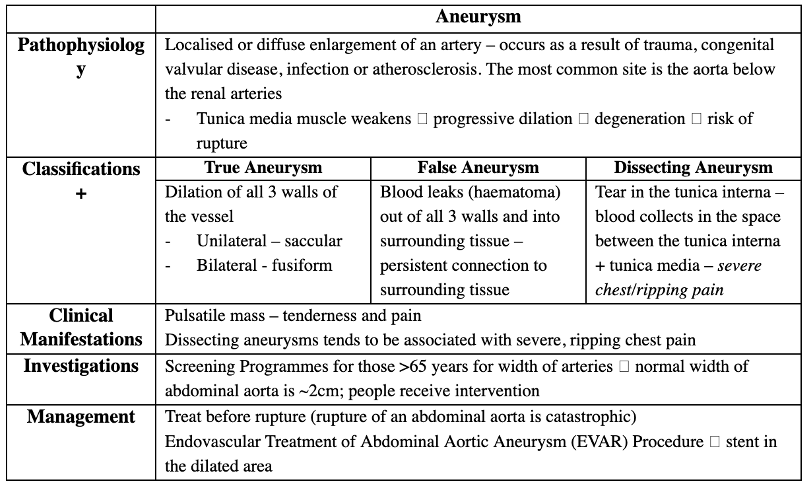

Answer: c) Dissecting Aneurysm

Explanation:

A dissecting aneurysm occurs when there is a tear in the tunica interna of the vessel wall, allowing blood to collect between the tunica interna and the tunica media, causing a separation of the vessel layers. This condition is classically associated with severe, ripping chest pain that may radiate to the back. The patient’s presentation and CT findings suggest a dissecting aneurysm, which is often seen in the aorta, especially in patients with a history of hypertension.

Why not the other options?

a) True Aneurysm: A true aneurysm involves the dilation of all three layers of the vessel wall. The description in the question does not match the characteristics of a true aneurysm, which would present with a more gradual and less dramatic onset of symptoms.

b) False Aneurysm: A false aneurysm involves a hematoma formed by blood leaking out of the vessel but maintaining a persistent connection to the vessel. This is typically seen as a pulsatile mass but does not involve a tear between the internal and medial layers of the vessel wall like a dissecting aneurysm does.

d) Fusiform Aneurysm: A fusiform aneurysm is a bilateral dilation of the vessel, giving it a spindle-like shape, often involving the full circumference of the vessel. This is typically seen in true aneurysms but is not described by the “tearing” pain associated with a dissection.

e) Saccular Aneurysm: A saccular aneurysm is unilateral and typically occurs as a localised dilation on one side of the vessel. It does not involve the separation of layers seen in a dissecting aneurysm.

(*)

Question 29:

Answer: a) Doppler Ultrasound of the brachial and dorsalis pedis arteries (Ankle-Brachial Index)

Explanation:

The patient’s symptoms are consistent with peripheral artery disease (PAD), specifically Atherosclerosis Obliterans:

• The patient’s intermittent claudication (pain on exertion) and the findings of coldness and pallor in the leg are signs of impaired blood flow due to arterial occlusion. This is typically caused by atherosclerosis.

• The Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI), measured using Doppler Ultrasound, is a non-invasive test that compares the blood pressure at the ankle to the blood pressure at the arm. A reduced ABI indicates arterial occlusion and can assess the severity of PAD.

Why not the other options?

b) CT Angiography (CTA): While CTA is the gold standard for visualising arterial occlusions and is commonly used in more advanced or complex cases, the ABI is a simpler and first-line diagnostic tool for confirming Atherosclerosis Obliterans in patients presenting with intermittent claudication. CTA would be used if more detailed imaging is needed after initial assessment.

c) Embolectomy: This is a surgical procedure used to remove clots (emboli) from arteries. It would be used in the case of acute limb ischemia caused by an embolism, but this patient’s presentation suggests chronic PAD due to atherosclerosis rather than an acute clot.

d) Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty (PTA): PTA is a treatment used to open upblocked arteries by inflating a balloon at the site of the occlusion. While PTA may be required if the condition progresses, Doppler Ultrasound (ABI) is the most appropriate first-step test to confirm the diagnosis before deciding on the treatment approach.

e) Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA): MRA is another imaging technique for assessing vascular structures, similar to CTA, and is used for visualising arterial occlusions. However, it is not the first-line diagnostic tool in the initial assessment of Atherosclerosis Obliterans. Doppler Ultrasound (ABI) is preferred as the initial non-invasive test for PAD.

Question 30:

Answer: a) LDL invasion into the tunica intima followed by oxidation and monocyte attraction, leading to foam cell formation

Explanation:

The correct answer is a, as this describes the early steps in the formation of fatty streaks, which are the initial lesions in atherosclerosis.

• LDL invasion and oxidation: When the endothelium is damaged (due to factors like hypertension, hyperglycaemia, or smoking), LDLs from the bloodstream invade the tunica intima. These LDLs are then oxidised by free radicals released by infiltrating monocytes.

• Monocyte attraction: The oxidised LDLs attract more monocytes, which migrate into the intima through a process called diapedesis.

• Foam cell formation: As monocytes engulf the oxidised LDLs, they turn into foam cells, which accumulate and form fatty streaks. These streaks are the earliest visible form of atherosclerotic lesions.

Why not the other options?

b) Platelet aggregation and smooth muscle proliferation: While platelet aggregation does occur in the later stages of plaque rupture (after the fatty streaks have formed), it is not involved in the formation of fatty streaks. Smooth muscle proliferation also follows the formation of foam cells, as it contributes to the development of the fibrous plaque (atheroma), which is a more advanced stage of atherosclerosis.

c) Chronic post-prandial hyperglycaemia causing endothelial injury: Chronic hyperglycaemia can indeed cause endothelial dysfunction and glycocalyx damage, but this is part of the long-term endothelial dysfunction that contributes to the progression of atherosclerosis, rather than the initial formation of fatty streaks.

d) Calcium deposition within the fibrous plaque: Calcium deposits occur in later stages of atherosclerosis, often contributing to plaque stabilisation, not the early fatty streak stage. Calcium deposits appear within the fibrous plaque and can be assessed on coronary angiograms to help quantify the level of plaque calcification.

e) Dysfunction of endothelial nitric oxide synthesis: While impaired nitric oxide (NO)synthesis due to endothelial dysfunction is an important aspect of vasomotor dysfunctionand overall atherosclerosis progression, it does not directly contribute to the formation of fatty streaks. NO deficiency impairs vasodilation and increases the risk of thrombosis but is not involved in the initial plaque formation.

Question 31:

Answer: b) Grade 2 Hypertensive Retinopathy, initiate treatment for hypertension and assess cardiovascular risk using QRISK3

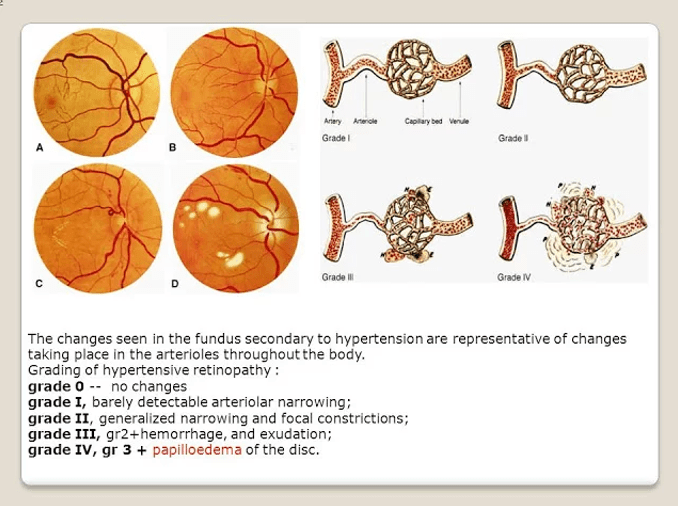

Explanation:

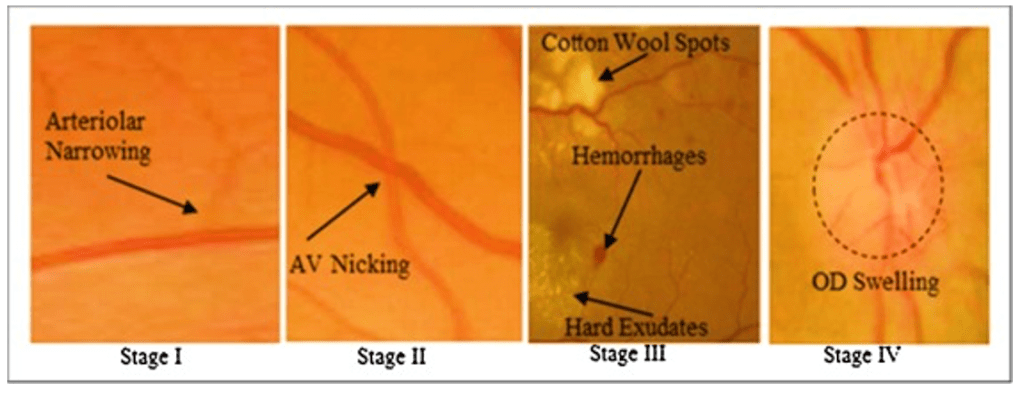

The patient’s retinal findings are consistent with Grade 2 Hypertensive Retinopathy, which involves tortuosity of the retinal arteries, increased reflectiveness, and arteriovenous nipping (thickened arteries crossing veins). According to the Keith-Wagener-Barker (KWB) grading system, this is classified as Grade 2.

In this case, the appropriate next steps are:

• Initiate treatment for hypertension: Managing hypertension is key in preventing further damage and complications.

• Assess cardiovascular risk using QRISK3: This tool helps assess the risk of stroke, coronary artery disease (CAD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and vascular dementia, allowing for appropriate treatment and monitoring.

Why not the other options?

a) Grade 1 Hypertensive Retinopathy, monitor blood pressure and lifestyle, recheck in 6 months: Grade 1 would involve minimal changes such as mild tortuosity of arteries and increased reflectiveness, but Grade 2 is more advanced and warrants active treatment and risk assessment rather than just monitoring.

c) Grade 3 Hypertensive Retinopathy, initiate antihypertensive therapy immediately and perform investigations for secondary causes of hypertension: While Grade 3includes flame-shaped haemorrhages and cotton wool exudates, the patient in the scenario only presents with signs of Grade 2, not Grade 3. Grade 3 would indeed require more urgent intervention, but the patient’s findings are not that severe.

d) Grade 4 Hypertensive Retinopathy, refer urgently for ophthalmology review due to risk of vision loss: Grade 4 includes papilledema (blurry optic disc margins), which is the most severe form of hypertensive retinopathy and would necessitate urgent referral. This patient, however, does not show signs of papilledema, so this option is not correct.

e) No retinopathy, continue monitoring blood pressure without changes to management: The patient does have signs of hypertensive retinopathy (Grade 2), so monitoring alonewithout adjusting the hypertension treatment and conducting further cardiovascular risk assessment would not be appropriate.

Question 32:

Answer: a) Vascular – Coarctation of the aorta, Chest X-ray showing rib notching

Explanation:

The patient’s findings, including delayed femoral pulses, upper limb hypertension, lower limb hypotension, and rib prominence, are classic signs of Coarctation of the Aorta. This congenital condition involves a narrowing of the aorta, typically located just after the branching of the subclavian arteries. It leads to a significant difference in blood pressure between the upper and lower limbs. The rib notching seen on a chest X-ray is a hallmark of long-standing coarctation, caused by collateral circulation (engorgement of intercostal arteries).

Diagnosis:

The most appropriate diagnostic test for Coarctation of the Aorta is a Chest X-ray to assess for rib notching and potentially a CT angiogram or MRI angiogram for definitive assessment of the aortic narrowing.

Why not the other options?

b) Renovascular Disease – Renal artery stenosis, Doppler ultrasound of renal arteries: While renal artery stenosis can cause hypertension, it is less likely to cause the specific findings of upper-lower limb blood pressure discrepancy and rib notching. Doppler ultrasound of the renal arteries would be helpful for renovascular disease, but it doesn’t explain the other features in this case.

c) Endocrine Hypertension – Primary hyperaldosteronism, Plasma aldosterone/renin ratio: Primary hyperaldosteronism could cause hypertension but does not typically cause upper-lower limb blood pressure discrepancy or rib notching. The diagnostic workup for this condition would involve the aldosterone/renin ratio, but it is unlikely to explain the physical examination findings here.

d) Drug-Related Hypertension – Alcohol abuse, Urine drug screen: Alcohol abuse may contribute to hypertension but is not likely to cause delayed femoral pulses or rib notching. Additionally, the clinical presentation (including leg cramps and the blood pressure discrepancy) points to a vascular issue rather than a drug-related cause.

e) Connective-Tissue Disease – Scleroderma, Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) test: Scleroderma could potentially contribute to hypertension, but it typically presents with skin changes (such as tightening of the skin) and other systemic symptoms like Raynaud’s. The findings of delayed femoral pulses and rib notching are not characteristic of scleroderma.

(*)

Question 33:

Answer: a) Tetralogy of Fallot, Surgery required in the first year of life

Explanation:

This infant’s symptoms, including cyanosis, failure to thrive, and respiratory distress, combined with the wide split S2, loud systolic murmur, and boot-shaped heart on chest X-ray, are highly suggestive of Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF). TOF is the most common cyanotic congenital heart disease and involves four defects:

1. Right ventricular outflow obstruction (pulmonary stenosis)

2. Right ventricular hypertrophy

3. Ventricular septal defect (VSD)

4. Overriding aorta

These defects lead to cyanosis due to deoxygenated blood being shunted into the systemic circulation. Surgery is the definitive treatment, typically required within the first year of lifefor complete repair.

Why not the other options?

b) Coarctation of the Aorta, Surgical repair in neonates: Coarctation typically presents with upper-lower blood pressure discrepancies, reduced femoral pulses, and cardiogenic shock if severe. It does not typically cause cyanosis at birth, and boot-shaped heart on X-ray is not characteristic of this condition.

c) Pulmonary Valve Stenosis, Balloon valvuloplasty: While pulmonary valve stenosis can present with a systolic murmur and S2 splitting, it does not typically cause cyanosis in neonates or a boot-shaped heart. Treatment is usually balloon valvuloplasty, but it is not the most likely diagnosis in this case.

d) Transposition of Great Arteries, Immediate prostaglandins at birth: Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) causes cyanosis immediately after birth due to the anatomical reversal of the aorta and pulmonary artery. However, the boot-shaped heart and wide split S2 are not typical findings in TGA, and prostaglandins are used to maintain patency of the ductus arteriosus until surgery is performed, typically within the first few days of life.

e) Atrial Septal Defect, Surgical closure of the hole: ASD typically presents with asymptomatic cases or mild symptoms such as failure to thrive, but it does not cause cyanosis or a boot-shaped heart. An ejection systolic murmur and split S2 may be present, but it does not explain the severe cyanosis and other findings in this case.

Question 34:

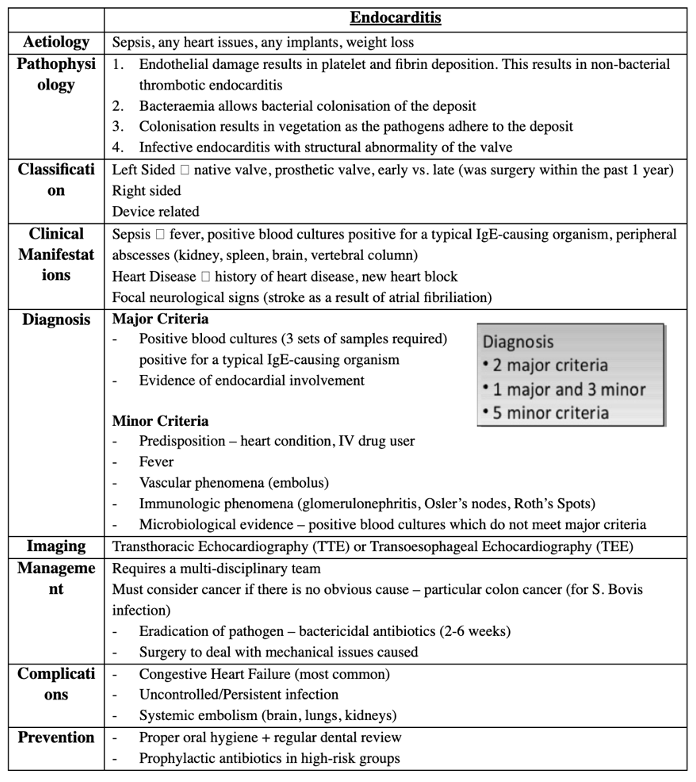

Answer: a) The patient likely meets the major criteria for infective endocarditis, as he has positive blood cultures and evidence of endocardial involvement.

Explanation:

This patient meets the major criteria for infective endocarditis (IE) based on the following:

1. Positive blood cultures: The patient’s fever, weight loss, and potential for infection point toward sepsis caused by a bacterial infection. Blood cultures (3 sets from different sites) are essential for confirming the diagnosis and constitute one of the major criteria.

2. Evidence of endocardial involvement: The echocardiogram reveals vegetations on the mitral valve, indicating active endocardial infection. This constitutes the second major criterion.

Why not the other options?

b) The blood cultures are a key component of the major criteria. Imaging alone (such as echocardiography) cannot confirm the diagnosis of infective endocarditis without the additional requirement of positive blood cultures or other major criteria.

c) The patient has a history of heart disease (rheumatic heart disease), which qualifies as predisposition for IE. He has also experienced fever, and vegetations were seen on echocardiography. This means he likely meets both major and minor criteria, not just the minor criteria.

d) Osler’s nodes and Roth’s spots are minor criteria for infective endocarditis, not major criteria. The presence of these findings would contribute to the diagnosis but would not be sufficient by themselves to meet the major criteria.

e) New heart block can be a manifestation of IE but is not considered a major or minor criterion by itself unless there is evidence of specific endocardial involvement or embolic phenomenon. This patient’s new murmur and vegetations on the valve are more indicative of endocardial involvement.

(*)

Question 35:

Answer: b) The narrowed aortic valve increases left ventricular pressure, causing concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle and eventually leading to heart failure due to impaired left ventricular filling.

Explanation:

In aortic stenosis, the narrowing of the aortic valve increases left ventricular (LV) pressureduring systole as the heart works harder to overcome the resistance caused by the stenotic valve. This results in concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle, where the heart muscle thickens to compensate for the increased pressure.

As the hypertrophy progresses, the LV becomes less distensible and struggles to fill properly during diastole. This impaired filling contributes to reduced cardiac output, which ultimately results in heart failure. Additionally, the reduced coronary artery perfusion due to the higher pressures in the left ventricle can lead to myocardial ischemia, further worsening heart function.

Why not the other options?

a) This statement is incorrect because aortic stenosis increases afterload (resistance against the left ventricle during systole) rather than decreasing it. The higher afterload leads to increased LV pressure, which in turn increases myocardial oxygen demand. Reduced coronary artery perfusion follows, which worsens myocardial ischemia.

c) While the Frank-Starling mechanism initially helps maintain cardiac output by increasing preload and contractility, it becomes insufficient as the LV loses its ability to compensate with increasing hypertrophy. Over time, this leads to heart failure, not an improvement in cardiac output.

d) While right heart failure may eventually occur as a consequence of left heart failure, it is secondary to the increased pressure and congestion in the pulmonary circulation due to impaired left ventricular filling. It is not directly caused by a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction in the early stages of aortic stenosis.

e) Although reduced coronary artery perfusion is a result of the high pressures in the LV, it does not cause complete myocardial ischemia in the early stages of aortic stenosis. Rather, it contributes to chronic myocardial ischemia and progressive heart failure over time. Sudden death would typically be caused by arrhythmias or severe decompensation, not from complete ischemia.

Question 36:

Answer: b) Mitral Regurgitation

Explanation:

• The patient’s symptoms of shortness of breath, fatigue, and palpitations are common in Mitral Regurgitation (MR), where there is backflow of blood from the left ventricle into the left atrium during systole. This leads to increased left atrial and ventricular pressures, resulting in pulmonary congestion and right heart strain, which may explain the patient’s symptoms.

• The pansystolic murmur heard best at the apex, along with a hyperdynamic apex beat and displaced apical impulse, are classic findings in Mitral Regurgitation. The murmur occurs as blood regurgitates into the left atrium, and the hyperdynamic apex beat reflects increased left ventricular work.

• Pulmonary congestion (fluid in the lungs) is consistent with the elevated pressure in the left side of the heart, which can back up into the lungs, leading to symptoms like shortness of breath.

Why not the other options?

a) Mitral Stenosis would be more likely if the patient had dyspnoea, haemoptysis, and signs of pulmonary oedema, but the murmur would typically be mid-diastolic with an opening snap, rather than a pansystolic murmur. The findings of right heart failure (e.g., ascites, hepatomegaly) would also be more common in severe mitral stenosis.

c) Aortic Regurgitation (AR) can present with dyspnoea, palpitations, and fatigue, but it would typically show an early diastolic murmur (high-pitched and decrescendo), best heard at the left sternal edge. Additional signs like collapsing pulse (Watson’s Water Hammer pulse) or head bobbing (De Musset’s sign) are more specific to AR and are not present here.

d) Tricuspid Regurgitation is more likely to cause right-sided heart failure, including elevated JVP, ascites, and hepatomegaly. The murmur of tricuspid regurgitation is typically pansystolic and heard best at the lower left sternal edge, often increasing with inspiration, which differs from MR.

e) Pulmonary Regurgitation typically presents with symptoms related to pulmonary hypertension or right ventricular failure, including RV dilation and tricuspid regurgitation. The murmur would be early diastolic and heard at the left sternal edge during deep inspiration, and the patient’s clinical presentation does not fit this pattern.

Question 37:

Answer: Pulmonary Stenosis

Explanation: Pulmonary stenosis (PS) refers to narrowing of the pulmonary valve or right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), which makes it harder for blood to move from the right ventricle (RV) to the pulmonary artery. Normally, during systole, the RV contracts, pushing blood through the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery to be oxygenated in the lungs. In PS, the valve is stiff or narrowed, meaning less blood can pass through it. Consequently, the RV must work harder to push blood forward, leading to increased pressure inside the RV (right ventricular hypertrophy – RVH). Because blood is forced through a narrowed opening, it moves turbulently. This creates a systolic crescendo-decrescendo murmur (diamond-shaped) heard best at the upper left sternal border. During inspiration, negative pressure in the chest causes increased venous return to the right heart. This increases blood volume going into the RV, making the murmur louder

A) is incorrect because although aortic stenosis also causes a crescendo-decrescendo murmur, it’s best heard at the right upper sternal border and unlike PS, it radiates to the carotids. It also causes left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), not RVH.

B) is incorrect because mitral Stenosis causes a diastolic murmur, not systolic and is best heard at the apex, not at the upper left sternal border.

D) is incorrect because tricuspid Stenosis causes a diastolic murmur, not systolic and leads to right atrial enlargement, not RVH.

E) is incorrect because atrial septal defect presents with a fixed split S2, not a crescendo-decrescendo murmur and usually doesn’t cause pressure overload on the RV unless very severe.

Question 38:

Answer: B) Increased pulmonary venous pressure leading to pulmonary congestion

Explanation: The symptoms and findings all point to Mitral stenosis, which is a narrowing of the mitral valve,preventing normal blood flow from the left atrium (LA) to the left ventricle (LV). Normally, blood from the lungs enters the LA, then flows into the LV via the mitral valve. If the mitral valve is narrowed (stenotic), blood has difficulty passing through and the LA must work harder, leading to increased left atrial pressure. This causes blood to back up into the pulmonary veins, increasing pulmonary capillary pressure, leading to dyspnoea, pulmonary oedema, and haemoptysis. An opening snap occurs because the mitral valve is stiff, but when it finally opens in diastole, it does so forcefully, producing an opening snap. Left atrial enlargement occurs because it has to generate more pressure to push blood through the stenotic mitral valve. Over time, this enlarges the LA, increasing the risk of atrial fibrillation (AF). AF worsens MS symptoms by reducing atrial contraction, leading to even less blood flow into the LV.

A) is incorrect because mitral stenosis affects left atrial pressure, not afterload and left ventricular hypertrophy occurs in aortic stenosis, not MS.

C) is not the best answer because while long-standing MS can cause right heart failure, the primary problem is left atrial hypertension and pulmonary congestion.

D) is incorrect because preload isn’t significantly reduced early on.

E) is incorrect because IMS doesn’t directly increase left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP). Instead, LA pressure is elevated.

Question 39:

Answer: A) Decreased cardiac output due to left ventricular outflow obstruction

Explanation: This history and findings are all indicative of aortic stenosis. In aortic stenosis the aortic valve narrows, restricting blood flow from the left ventricle (LV) to the aorta. Consequently, the LV must generate higher pressure to eject blood, leading to left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). As the valve area decreases (<1 cm² is severe AS), the LV struggles to maintain cardiac output (CO). Syncope occurs due to reduced cardiac output leading to inadequate cerebral perfusion. Angina occurs due to LVH increasing oxygen demand, while aortic stenosis reduces coronary perfusion. A crescendo decrescendo murmur occurs because blood is forced through the narrowed valve, creating turbulent flow during systole.

B) is incorrect because right ventricular hypertrophy occurs in conditions with increased pulmonary resistance, such as pulmonary hypertension and chronic lung diseases. This patient’s symptoms and findings are not due to right heart strain but due to left ventricular outflow obstruction as show by the echocardiography.

C) is incorrect as while left atrial pressure does increase in severe aortic stenosis, atrial fibrillation is not the primary mechanism behind this patient’s symptoms. AS primarily affects the left ventricle, causing syncope, angina, and dyspnoea due to low cardiac output rather than atrial arrhythmias. Atrial fibrillation is more commonly associated with mitral valve disease (e.g., mitral stenosis), not AS.

D) is incorrect because mitral stenosis (MS) causes diastolic dysfunction due to obstruction at the mitral valve, not the aortic valve It presents with a diastolic murmur, not a systolic ejection murmur. MS leads to pulmonary congestion, left atrial enlargement, and atrial fibrillation, but this patient has aortic stenosis, which affects the left ventricle, not the left atrium.

E) is incorrect because pulmonary artery stenosis affects the right heart, not the left heart. This patient’s symptoms are due to left ventricular outflow obstruction, not right ventricular failure. Pulmonary artery stenosis presents with right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) and a systolic murmur at the left upper sternal border, which does not match this case.

Question 40:

Answer: D) Streptococcus viridians causing subacute infective endocarditis

Explanation: This patient has subacute infective endocarditis (IE), which commonly occurs in individuals with pre-existing valvular disease (e.g., mitral valve prolapse, rheumatic heart disease). Streptococci viridians (e.g., Streptococcus sanguinis) are part of the oral flora and cause subacute IE following dental procedures or minor bacteraemia. Clinical features of subacute IE are a low-grade fever, fatigue, new heart murmur (mitral valve most affected), Osler nodes (painful, immune complex deposition), Janeway lesions (non-tender embolic lesions), splinter haemorrhages, and Roth spots (retinal haemorrhages)

A) is incorrect because Coxiella burnetii causes culture-negative endocarditis, usually in patients with farm animal exposure (Q fever). This patient has positive blood cultures, making this incorrect.

B) is incorrect because Staphylococcus aureus causes acute infective often in IV drug users or prosthetic valves. Staph aureus has a rapid onset unlike this patient whose onset of symptoms began 2 weeks ago.

C) is incorrect because Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes IE in IV drug users, but this patient has a history of MVP, not IV drug use. Also, Pseudomonas is a Gram-negative rod, but this patient has Gram-positive cocci in chains.

E) is incorrect because rheumatic fever damages the mitral valve over decades. This patient has infective endocarditis, not rheumatic heart disease.

Question 41:

Answer: E) Pulmonary hypertension

Explanation: This history is describing tricuspid regurgitation, a valvular disease characterised by retrograde blood flow from the right ventricle into the right atrium during systole due to insufficient closure of the valve. Tricuspid regurgitation causes a pansystolic murmur at the left lower sternal border which increases with inspiration (Carvallo’s sign). The liver may be pulsatile liver venous congestion flowing back into the hepatic vein. JVD, ascites, and oedema are signs of right heart failure.

A) is incorrect because rheumatic fever primarily affects the mitral and aortic valves.

B) is incorrect because right ventricular infarction can cause TR, but it is less common than pulmonary hypertension.

C) is incorrect because Endocarditis causes TR, but usually in IV drug users with fever and septic emboli.

D) is incorrect because although carcinoid syndrome can cause TR, but it is rare and associated with flushing and diarrhoea.

Question 42:

Answer: A) Post-ductal narrowing of the aorta, leading to increased upper body perfusion and reduced lower body perfusion

Explanation: This child has coarctation of the aorta (CoA), a congenital narrowing of the aortic arch, occurring distal to the ductus arteriosus (post-ductal) and pre-ductal in others. Narrowing of the aorta increases resistance to blood flow. This leads to hypertension in the upper extremities (due to increased afterload) and hypoperfusion of the lower extremities (due to decreased blood flow past the coarctation). The body compensates by developing collateral circulation (intercostal arteries), which can cause rib notching on X-ray. The child has fatigue on exertion because reduced lower body blood flow limits exercise tolerance, leg pain/claudication due to poor perfusion, headaches/nosebleeds due to high upper body pressure.

B) is incorrect because malformation of the pulmonary valve leading to right ventricular hypertrophy describes pulmonary stenosis, which causes right-sided heart strain and cyanosis in severe cases. Coarctation is a left-sided lesion and does not primarily affect the right ventricle.

C) is incorrect because coarctation does not require a patent ductus arteriosus; in fact, closure of the PDA can worsen symptoms in severe infantile CoA.

D) is incorrect because abnormal mitral valve chordae leading to left atrial dilation and pulmonary congestion describes mitral regurgitation, which causes left atrial dilation and pulmonary congestion but does not cause differential blood pressures in the upper and lower extremities.

E) is incorrect because Atrioventricular septal defects (AVSDs) occur due to defective endocardial cushion formation and are common in Down syndrome. They cause left-to-right shunting and pulmonary over circulation, which are not the characteristic findings of Coarctation.

Question 43:

Answer: B) Obstruction of the right ventricular outflow tract leading to right-to-left shunting

Explanation: This infant has Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), the most common cyanotic congenital heart disease. It consists of four features: Pulmonary stenosis (RV outflow obstruction), Right ventricular hypertrophy (due to increased workload), Ventricular septal defect (VSD) (hole between ventricles) and an overriding aorta (aorta receives blood from both ventricles). Pulmonary stenosis increases resistance to right ventricular blood flow. This causes deoxygenated blood to bypass the lungs via the VSD into the aorta (right-to-left shunt). Consequently, less blood reaches the lungs for oxygenation, resulting in cyanosis. A harsh systolic ejection murmur occurs due to pulmonary stenosis at the left upper sternal border.

A) is incorrect because increased left-to-right shunting leading to pulmonary over circulation occurs in acyanotic heart defects like ventricular septal defect (VSD) and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). TOF has right-to-left shunting, not left-to-right.

C) is incorrect because TOF does not require a patent ductus arteriosus = for survival.

D) is incorrect because atrial septal defects cause left-to-right shunting initially and are not cyanotic at birth. A paradoxical embolism (stroke from venous clot reaching the brain) can occur if the ASD allows right-to-left shunting later in life (Eisenmenger’s syndrome).

E) is incorrect because left ventricular outflow obstruction leading to decreased systemic blood flow describes conditions like aortic stenosis or coarctation of the aorta. TOF is a right-sided lesion (pulmonary stenosis, not aortic stenosis).

Question 44:

Answer: C) Aortic stenosis

Explanation: This 72-year-old patient presents with progressive exertional dyspnoea, chest pain, and dizziness, which are the classic symptoms of severe aortic stenosis (AS). Exertional dyspnoea (shortness of breath) occurs due to increased left ventricular (LV) pressure leading to pulmonary congestion. Chest pain (angina) occurs due to the hypertrophy of the left ventricle leading to a higher oxygen demand with limited coronary perfusion. Syncope (near-fainting) is caused by fixed cardiac output that cannot increase during exertion. A Soft S2 occurs due to calcified, immobile aortic valve leaflets preventing normal closure. The most common causes of aortic stenosis are age-related calcific aortic stenosis (most common in elderly patients >65 years), bicuspid aortic valve (common in younger patients <65 years), rheumatic heart disease (less common than degenerative AS in the elderly).